Measuring Cognitive Distraction in the Automobile

Using cutting-edge methods for measuring brain activity in conjunction with driving performance, this research develops a methodology for measuring cognitive distraction associated with performing non-driving-related tasks while driving.

June 2013

Suggested Citation

For media inquiries, contact:

Tamra Johnson

202-942-2079

TRJohnson@national.aaa.com

Abstract

In this landmark study of distracted driving, the AAA Foundation challenges the notion that drivers are safe and attentive as long as their eyes are on the road and their hands are on the wheel. Using cutting-edge methods for measuring brain activity and assessing indicators of driving performance, this research examines the mind of the driver, and highlights the mental distractions caused by a variety of tasks that may be performed behind the wheel.

By creating a first-of-its-kind rating scale of driver distractions, this study shows that certain activities – such as talking on a hands-free cell phone or interacting with a speech-to-text email system – place a high cognitive burden on drivers, thereby reducing the available mental resources that can be dedicated to driving. By demonstrating that mentally-distracted drivers miss visual cues, have slower reaction times, and even exhibit a sort of tunnel vision, this study provides some of the strongest evidence yet that “hands-free” doesn’t mean risk free.

Background

- Distracted driving is a significant highway safety threat, responsible for well over 3,000 fatalities each year.

- There are three main sources of driver distraction:

- Visual (eyes off the road)

- Manual (hands off the wheel)

- Cognitive (mind off the task)

- Of these, cognitive distraction has been the hardest to study.

- Prevailing assumptions have held that “hands-free” = safe:

- 66% of licensed drivers say driver use of hand-held cell phones is unacceptable; 56% say hands-free is acceptable.

- New speech-based in-vehicle technologies and infotainment systems have proliferated.

- The AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety set out in 2011 to study this issue and investigate potential sources of cognitive distractions for drivers.

New Study: Measuring Cognitive Distraction in the Automobile

Objectives:

- Isolate the cognitive elements of distracted driving;

- Evaluate the amount of cognitive workload caused by various tasks performed by drivers; and

- Create a rating scale ranking tasks according to how much cognitive distraction they cause.

Methods:

Three experiments were performed:

- Laboratory

- Driving Simulator

- Instrumented Vehicle

Several measures were used to assess cognitive workload, such as:

- Subjective workload ratings (survey)

- Brake reaction time and following distance

- Reaction time & accuracy to peripheral light detection test

- Brainwave (EEG) activity

- Eye and head movements

Six common driver tasks were analyzed in each experiment

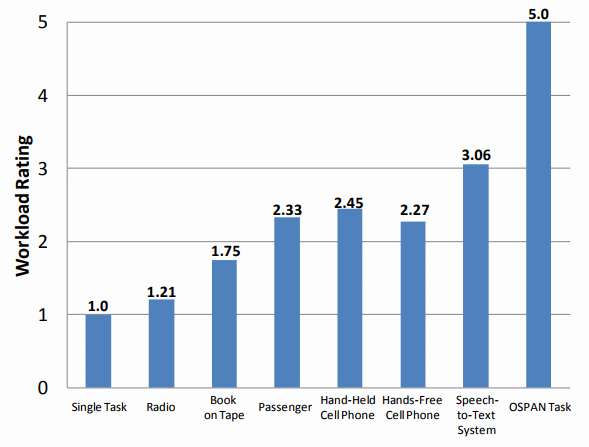

A seventh and eighth condition – non-distracted driving, and a complex series of math and verbal problems (OSPAN task) – were included to anchor the low and high ends of the rating scale, respectively.

Measurements from all experiments were standardized to create one rating scale

Key Findings

- Even when a driver’s eyes are on the road and hands are on the wheel, sources of cognitive distraction cause significant impairments to driving, such as:

- Suppressed brain activity in the areas needed for safe driving;

- Increased reaction time (to peripheral detection test and lead vehicle braking);

- Missed cues and decreased accuracy (to peripheral detection test); and

- Decreased visual scanning of the driving environment (tunnel vision, of sorts).

- Driver interactions with in-vehicle speech-to-text systems (such as the infotainment offerings in many new vehicles) create the highest level of cognitive distraction among the tasks assessed.

- Simply put: “hands-free” does not mean risk free!

Cognitive Distraction Rating Scale

The scale to the left ranks the six common driver tasks according to the amount of cognitive workload they impose on drivers. The two anchor conditions (single-task non-distracted driving, and the complex OSPAN math and verbal task) represent the low (1) and high (5) ends of the scale, respectively. The other scores are standardized from the three experiments, and demonstrate that while some tasks, like listening to the radio, are not very distracting, others – such as maintaining phone conversations and interacting with speech-to-text systems – place a high cognitive demand on drivers and degrade performance and brain activity necessary for safe driving.

Suggested Citation

For media inquiries, contact:

Tamra Johnson

202-942-2079

TRJohnson@national.aaa.com