Perceived Social Support Differences between Male and Female Older Adults who have Reduced Driving: AAA LongROAD Study

The research in this brief examines perceived social support among older drivers who have recently reduced their driving.

February 2020

Suggested Citation

Abstract

Introduction

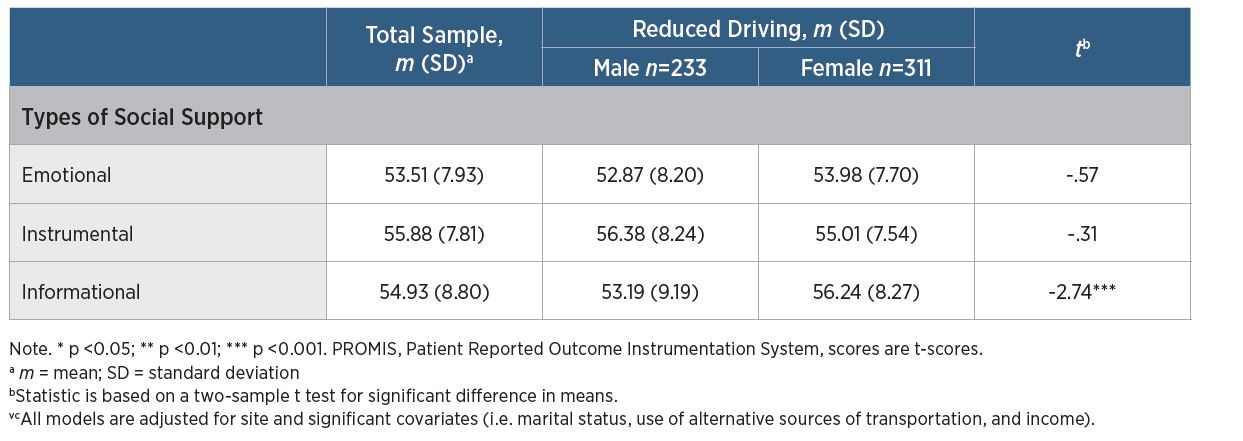

Many older adults have reduced their driving behaviors (e.g., restrict driving to daytime, short trips, or familiar locations) because of health issues, such as chronic illness, medication-related side effects, poor vision, and declines in physical and cognitive abilities. Reducing driving is often the first step in the process of stopping driving (i.e., driving cessation), and it can lead to declines in life satisfaction. Older adults who stop driving experience higher levels of depression, are less likely to participate in social activities, and are less able to manage their chronic health problems. Interventions that improve social support through strengthening networks and building support have been found to increase older adults’ overall life satisfaction. The research in this brief examines perceived social support among older drivers who have recently reduced their driving. Findings suggest that older men and women, who have reduced driving, report similar levels of instrumental and emotional support, however, men report lower levels of informational support than women do.

Key Findings

- 544 LongROAD participants reported reducing driving in the past year, less than one-fifth (18.2% of the total sample)

- Respondents reported high levels of social support overall

- Men reported lower levels of informational support than women

Methodology

Data came from the AAA Longitudinal Research on Aging Drivers (LongROAD) study, a prospective cohort study of 2,990 drivers aged 65-79 years in five sites in the United States (US), including: Ann Arbor, MI; Baltimore, MD; Cooperstown, NY; Denver, CO; and San Diego, CA.

The sample for this brief includes baseline data of AAA LongROAD study participants who reported that they had reduced driving (yes/no) in any way in the past year (Li, Eby, Santos, et al., 2017; Marshall, Man-Son-Hing, Charlton, 2013).

Social support in this study is defined as “aid and assistance exchanged through social relationships and interpersonal transactions,” and it may moderate decreases in life satisfaction that occur because of driving cessation (House, 1981). This study used the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) measures to examine emotional, instrumental, and information social support (Northwestern University, 2017).

Results

The research examined how three types of perceived social support – emotional, instrumental, and informational – differed between male and female among older adult drivers who reduced their driving in the past year. Respondents reported high levels of social support overall. Findings suggest that men and women report similar levels of emotional and instrumental support, but that men report lower levels of informational support than women. Thus, there may be a need to prioritize providing older adult men with informational social support (i.e., advice, suggestions, or helpful information about life decisions) in interventions that aim to enhance life satisfaction among those who have reduced their driving. Not being able to drive threatens adults’ sense of independence and emotional well-being, and also limits their ability to maintain social ties, remain active and engaged, and manage healthcare (Mezuk & Rebok, 2008; Stanford, Mielenz, DiMaggio, et al., 2015; Curl, 2014). Programs to improve social support often focus on building a closer network among members, increasing the frequency and duration of spending time with peers and family, and increasing emotional support could reduce the threats that arise from not driving (Roth et al., 2005).

Suggested Citation